-

1.1 Lloyd Gaines

Lloyd Gaines had won his case. Speaking to reporters, Gaines said he was pleased with the result and looked forward to attending the Missouri School of Law in the fall of 1939.

The Gaines v Canada decision was a major triumph and significant steppingstone for the Civil Rights movement. No longer did African-Americans in Missouri have to choose to be educated elsewhere when seeking degrees not offered to them in their home state. This was decided in the Murray v Pearson case three years prior, but the Gaines case had national implications since it was decided by the US Supreme Court.

-

1.2 News Article About US Supreme Court Justices Rule in Favor of Lloyd Gaines by 6 to 2 Vote in The Call Newspaper

Following the decision, northern newspapers hailed it as “the Supreme Court speaking out in defense of the quality of human rights.”

The Kansas City Call, one of the leading black newspapers in Missouri, declared, “If keeping the races separate is so important to Missourians that coeducation is unthinkable then let them count the cost!” The NAACP’s long-term plan for casting financial burden upon the Jim Crow states was now a reality.

-

1.3 John D. Taylor, Democrat, MO House of Representatives, 39th District

However, the State of Missouri was not going to go down without a fight. In mid- January, 1939, John D. Taylor, a representative from Keytesville, MO, introduced a bill in the Missouri legislature designed to postpone integration of the University. Taylor, chairman of the House Appropriations committee, proudly called himself “an unreconstructed rebel.”

Taylor’s proposal, House Bill No. 195, authorized Lincoln University to “establish whatever graduate and professional schools are necessary to the equivalent of the University of Missouri.”

-

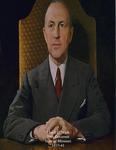

1.4 Lloyd C. Stark, 39th Governor of State of Missouri, 1937-1941

After weeks of debate Taylor’s proposal, House Bill No. 195 was passed and signed by Governor Lloyd Stark.

-

1.5 Sherman D. Scruggs, 11th President of Lincoln University, 1938-1956

The LU Board of Curators ordered its president, Sherman Scruggs, to have a law school up and running and ready for Lloyd Gaines by September 1, 1939. This task seemed insurmountable; establishing a law school on an equal par with that of MU in eight months would, in the least, be miraculous.

-

1.6 School of Law, Lincoln University

Another dilemma also had to be dealt with; Lloyd Gaines was determined to attend law school, not just anywhere but at the University of Missouri.

Shortly after the Supreme Court decision, Lloyd Gaines left his civil service job in Michigan and returned home to St. Louis, arriving on New Year’s Eve, 1938. In the meantime, to pay his bills, he took a job as a filling station attendant.

On January 9, 1939, Gaines spoke to the St. Louis chapter of the NAACP. He told them he stood “ready, willing, and able to enroll at MU.” Gaines later quit his gas station job. He explained to his family that the station owner substituted inferior gas and that he could not, in good conscience, continue to work there.

In the meantime, the state Supreme Court sent the Gaines case back to Boone County to determine whether the new law school at Lincoln would comply with the US Supreme Court’s requirement of “substantial equality.”

-

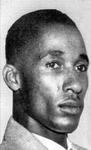

2.1 Lloyd Gaines close up image

Charles Hamilton Houston and other NAACP attorneys assembled in early October 1939 to take depositions in preparation for the hearing scheduled a week later in Columbia to determine whether the university had complied with the Gaines decision. Attorneys took depositions from all of the instructors of the new LU law school as their preparation for the court proceedings wound down.

The deposition of Lloyd Gaines was next. Attorneys planned to ask Gaines whether he considered Lincoln to be as good of a law school as Missouri and whether he planned to enroll. Called for questioning, Gaines did not respond.

He could not be located anywhere.

Lloyd’s mother, Callie Gaines, recalled that in January her son “left here to go to Kansas City to make a speech. That’s the last I saw of him.” While in Kansas City, Gaines spoke at the Centennial Methodist Church. He also looked for work, but not finding any caught a train for Chicago, telling people in Kansas City that he would stay a few days and return home.

-

2.2 Chicago YMCA

In Chicago, Lloyd rented a room at the YMCA; searching for employment for the next few weeks.

-

2.3 Eddie Mae Page, Friend of Lloyd Gaines in Chicago

During this time Lloyd Gaines took meals at the home of Eddie Mae Page; a friend from St. Louis. Running low on funds, he stayed at the Alpha Phi Alpha house where members took up a collection for him. On a rainy night, March 19, 1939, Lloyd Gaines told friends that he was going to buy stamps and would be right back.

To this day, Lloyd L. Gaines has never been located.

-

2.4 "The Strange Disappearance of Lloyd Gaines"

The May 1951 Ebony Magazine Article "The Strange Disappearance of Lloyd Gaines"

-

2.5 J. Edgar Hoover FBI Director 1935-72

Many theories, much speculation and a considerable amount of guessing can be attributed to the sudden and complete disappearance of Lloyd Gaines. Known as a loner and having a habit of taking off for days at a time, the whereabouts of Lloyd was not a concern to his family. In fact, Gaines wrote to his mother three weeks before he vanished that if she did not hear from him he would be okay.

Local and federal authorities, including the FBI were not notified immediately of his disappearance. Houston and the NAACP lawyers had not been in contact with Gaines for several months.

-

2. 6 Memorial for Lloyd Gaines, St. Peter's Cemetery, Normandy, St. Louis County, Missouri

What happened to Gaines? There are many ideas ranging from being murdered or lynched, being bribed to run away, or disappearing on his own to get away from the pressure of celebrity.

That final possibility was brought about by Dr. Greene, who claimed that a man who sounded like Gaines had phoned him while in Mexico and wished to meet. The man never showed up.

A recent theory is one of where Lloyd was kidnapped by opponents of the Gaines court decision who took him to Jefferson City and lynched him in McClung Park.

All of these theories are speculation and the fact remains that Lloyd Gaines’ whereabouts are a mystery to this day.

-

3.1 Lincoln University Law School

Despite his sudden disappearance, Lloyd Gaines’ impact had a resounding effect in many ways. The successful bridging of the gap from segregation to integration in the United States educational system was initiated because Gaines sought to be treated equally and fairly by the established powers. Much of the credit goes to the NAACP legal team, especially Charles Hamilton Houston’s dedication and expertise. However, without the initial action of Lloyd Gaines applying to the University of Missouri, there would have been no case.

Additionally, the Lincoln University School of Law was founded due to the results of the Gaines case. Although it was only in operation for 16 years, it provided opportunities for those who had been denied previously.

-

3.2 Lloyd L. Gaines/Marian O'Fallon Oldham Black Culture Center at University of Missouri

Lloyd Gaines’ memory has been honored most notably by the University of Missouri. In 1995, a law scholarship in his name was established at the institution. Also, in 2001, MU opened the Gaines/Oldham Black Culture at MU which shares his name.

-

3.3 University of Missouri awarded a law degree to Lloyd Gaines in 2006

In 2006, a law degree was posthumously awarded to Lloyd and accepted by his nephew, George Gaines.

-

3.4 University of Missouri Doctor of Law Degree to Lloyd Lionel Gaines

On May 13, 2006, University of Missouri awarded Lloyd Gaines Doctor of Law degree.

-

3.5 The Missouri State Supreme Court Conferred a Honorary Law License for Lloyd Gaines.

On September 28th, 2006, the Missouri State Supreme Court conferred a posthumous law license for Mr. Gaines.